The Galapagos Islands offer a rare peek at what the world might look like devoid of human interference. Known for their role in Darwin’s theory of evolution, the islands were impossible for me to visit without leaving changed.

I wish I could say it was my own curiosity that brought me to Galapagos, but I’d be lying. It was my mom. Seeing this legendary collection of islands had been a lifelong dream of hers; I just hitched a ride, more enamored by the idea of joining an expedition trip with National Geographic than with the thrill of visiting the destination itself. In fact, after I accepted the generous offer to be her bunkmate, I promptly hung up the phone and Googled “Galapagos Islands” to see where on earth they were located.

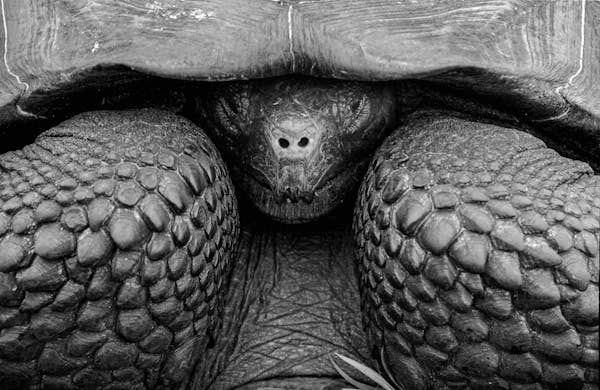

Roughly 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador, the Galapagos islands are nature at its most raw — fierce landscapes of volcanic rock, intensely saturated colors, and a harsh game of survival of the fittest. The islands somehow manage to be both barren and full.

When I first stepped onto Isla Fernandina, it was like I’d traveled through time. Estimated to be somewhere between 60,000 to 400,000 years old, Fernandina is the youngest island in the volcanic archipelago — and it showed. Beneath my feet the ground looked like thick ribbons of black lava still trying to ooze their way out to sea. The fact the island has an active volcano (which last erupted in 2018) didn’t help; even though I knew it was rock solid, I tread lightly, testing for any still-warm soft spots.

Oceanside, the charcoal-gray marine iguanas stacked themselves on similarly colored lava rocks to sunbathe and were only really visible when they expelled snorts of seawater through their nostrils. Down lower I saw brightly colored Sally Lightfoot crabs scuttling around and scavenging food from the rocks and tide. (What I didn’t see at the time, thank god, was the unfathomable amount of racer snakes between the rocks, hiding in wait.)

If there’s anything that gives you perspective on how easy we’ve got it as humans, it’s watching wild animals struggle to survive right in front of your eyes. I watched tensely as a baby bird was stolen right from under its nesting parent by a hawk, then miraculously saved, only to be accidentally and fatally dropped on a rock. On any given island, the remains of unfortunate animals and birds baked in the sun and disintegrated back into the sand.

On nearly every island they inhabited, but especially Isla Española, the sea lions came out to play. They hopped over to us, struck impossibly photogenic poses in front of our cameras, and even chased us on the beach. While snorkeling off of Isla Floreana, I had the most delightful surprise when a playful sea lion swam up to me and blew bubbles in my face. On other days spent on the other islands, I observed zippy penguins, searched for sea turtles, or came face-to-face with marine iguanas as they munched algae off the underwater rocks.

On land, my overwhelming memory is how colorful everything was, like someone had just dialed up the saturation and vibrancy on everything. Brick red dirt, bright green grass, iguanas with bold yellow and deep orange scales, flamingos with perfectly pink feathers, complex greys and browns, endless shades of black. I’d never seen such bright, rich colors before, and have yet to see them again since.

Being able to see such pristine examples of nature with such limited human interaction was a beautiful but hard pill to swallow. Even watching how our presence affected the wildlife on the islands was eye-opening. After observing such a raw display of what the world could look like without human interference, it was impossible not to see what a dramatic impact we’ve had on the earth. It made me evaluate how my everyday actions and choices affect the planet, and twelve years later these realizations are still guiding how I live, travel, and work, making me more conscious of my personal footprint, the effects of my presence on a destination, and the responsibility I have as a traveler and travel writer.

There is no other place on earth like Galapagos. Thanks to the archipelago’s remote location, the Galapagos Islands and its flora and fauna were able to evolve for millions of years without outside interference. Taking a trip here is like sneaking a look into a secret, untouched sliver of a truly natural world. Even now, after three hundred years of human visits, the ecosystems are miraculously still 95% intact — for now.

With this great privilege comes even greater responsibility to keep the islands as intact as possible as tourism continues to soar, lest we destroy the very things we are excited to experience. Always consider responsible, reputable companies, hotels, and tour operators that employ trained guides and eco-initiatives, and remember — you are the visitor in this world, leave it as you find it.

You may also like:

First-timer’s guide to the Galapagos Islands

Canada’s best wildlife experiences

How to reduce your use of plastic on a trip