Referenced by generations of globe-trotting travelers and kept on bookshelves as dusty, dog-eared souvenirs, guidebooks have played an influential role in dissecting and shaping travel culture for over 200 years.

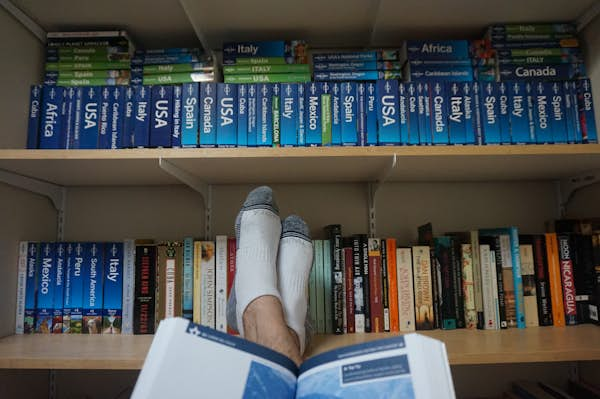

In contrast to the inherently fleeting attractions of the internet, these well-thumbed relics of grand tours and budget backpacking jaunts retain a nostalgic and romantic allure that’s hard to replicate online. Open a furrowed Lonely Planet and dozens of memories come pouring out: the faded coffee-stains, the cheap hostel reviews marked in yellow highlighter pen, the scribbled phone number of a gap-year sociology student you met in Cuzco in nineteen-ninety-something but never reconnected with.

The travel guidebook takes shape

The exact origin of guidebooks is murky. Travel memoirs have been written for as long as humans have been exploring the globe. However, what separates modern guidebooks from old-fashioned travelogues like The Travels of Marco Polo is the inclusion of practical information written with the intention of encouraging readers to follow in the writer’s footsteps.

An early pioneer of the art was Mariana Starke, an aspiring British poet and playwright who shared the same publisher as Jane Austen and Lord Byron. Starke’s 1802 book, Travels in Italy Between the Years 1792 and 1798 comprised a collection of travel memoirs that dispensed of overly romantic first-person descriptions of nature in favour of solid factual advice. Eager to smooth the passage for travelers brave enough to circumnavigate the battlefields of revolutionary France, Starke wrote up her observations of Italian churches and villas using a subjective rating system based on one to five exclamation marks.

Starke’s book languished as a little-used guide for over a decade, primarily because Europe was still embroiled in the Napoleonic Wars and worryingly short of congenial hotels. Things changed in 1815 when the Congress of Vienna ushered in a protracted period of peace, and European ladies and gentlemen of means, inspired by the poetic prose of writers like Byron, expressed an increasing desire to travel abroad.

As the map of Europe had been largely redrawn since Starke’s 1802 guide, the author – by then well into her 50s – produced a more comprehensive update. Published in 1820, Information and Directions for Travellers on the Continent covered Europe from Portugal to Russia and was stuffed with pithy advice on “tolerable” inns, how to hire a horse carriage and the variable state of the continent’s post-roads.

Starke’s second book struck a chord, not just with the public, but also with its British publisher, John Murray, a foresighted man who knew a ground-breaking idea when it landed on his desk (he later went on to publish Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species).

Guidebooks grow into a business

Inspired by Starke’s musings, Murray decided to get in on the travel guidebook business himself. In 1836, his Handbook for Travellers on the Continent ignited one of the world’s first guidebook series and quickly established a prototype for all books that followed. Murray borrowed several ideas from Starke, including organizing subsections into itineraries, sightseeing spots, and inn listings.

Quality was Murray’s hallmark. Demanding high standards of his writers and researchers, the “Murray Handbooks” with their trademark red covers and gold lettering were produced by a capable pool of scribes, some of whom were noted literary figures. Richard Ford, a graduate of Trinity College, Oxford, undertook two years of arduous research on horseback in Spain.

The resulting 1845 Murray’s Handbook to Spain quickly morphed into the Odyssey of travel guidebooks. By turns witty, opinionated, exhaustive and erudite, Ford’s book and sometimes prejudicial views on Spain helped put the country on the travel map. His priceless essays on Spanish music provide some of the earliest insights into the nascent art of flamenco, while his expert ruminations on art and history helped kick-start a love affair with Spain among British travellers that endures to this day.

Baedeker guidebooks’ beginnings

The rise of the Murray Handbooks in Britain coincided with the birth of another brand in Germany. Bookseller and publisher Karl Baedeker launched his first book, the inauspicious Travels along the Rhine from Mainz to Cologne, in 1832 based on information taken from an existing guide he had bought from a bankrupt publishing house. After refining his vision with ideas poached from Murray, the so-called “father of modern tourism” quickly hit on what became his best-selling formula: a guide that encouraged the burgeoning European intelligentsia to travel independently without an expensive assemblage of servants and paid guides.

Some of Mr Baedeker’s working methods are familiar today. He undertook his meticulous research covertly usually traveling on his own. “The entire contents of the book are based exclusively on personal experience,” he wrote as a foreword to all his early editions. With the books fanning out to cover multiple countries including France and Britain by the 1840s and 50s, personal research became a tall order. Baedeker, who was proficient in ten languages, did much of it solo and ultimately overreached himself. He died aged 57 in 1859, reputedly from overwork.

Murray Handbooks was sold off in 1900, but Baedeker, under the direction of Karl’s son Fritz, continued to flourish, publishing an astounding 233 guides to over 40 countries between 1900 and 1914. Faultlessly accurate, though jarringly un-PC by modern-day standards, many of the books went on to become classics. The Palestinian guide was mined extensively by TE Lawrence (of Arabia) during his archaeological digs in the Middle East, while the encyclopedic 1929 Egyptian tome is widely considered to be one of the most accomplished guidebooks ever produced. Today, rare first editions of classic Baedekers can fetch up to US$5,000 at auction.

So ubiquitous were the company’s books that they were often name-checked by contemporary novelists and playwrights. EM Forster converted them into a simile (“their noses were as red as their Baedekers”) while TS Eliot referenced them in a poem (“Burbank with a Baedeker: Bleistein with a Cigar”). By the 1920s, the verb “to Baedeker” had become a synonym for ‘to travel’.

Events took a sinister turn in World War II when the Nazis used Baedeker’s 1937 Great Britain guide to pinpoint monuments in historic British cities for devastating bomb attacks. The so-called “Baedeker raids” were carried out in retaliation to the British bombing of Lübeck in March 1942. “We’ll go out and bomb every building in Britain given three stars in the Baedeker,” Nazi propagandist Gustav Braun von Stumm is said to have proclaimed. Cultural sites in Exeter, Bath and York were all subsequently hit. Reprisals were swift. The following year British bombers destroyed Baedeker’s publishing house in Leipzig.

Travel comes to the masses

With the onset of mass tourism in the 1960s and 70s, guidebooks proliferated, most notably at the budget end of the market. Mega-brands grew from humble DIY roots to feed a new generation of freewheeling explorers christened “backpackers.” Arthur Frommer’s self-published GI’s Guide to Traveling in Europe (1955), a thin volume initially tailored for American soldiers, morphed into Europe on $5 A Day. Let’s Go guides arose from an idea hatched at Harvard University in 1960. The books, written by students for budget-seeking Americans, served as a fertile breeding ground for young authors, some of whom later graduated to careers in screenwriting, journalism and politics, including travel essayist Pico Iyer.

The biggest new innovators, Lonely Planet, emerged after founders Tony and Maureen Wheeler turned a cheap trip across Asia into a multimillion-dollar travel business whose guidebooks were so influential they became known as travel “bibles.” The Wheelers’ initial 1973 book, Across Asia on the Cheap packed more than a dozen countries into just 94 pages and included gems of hippy-era budgetary advice (“In Afghanistan in particular you can get stoned just taking a deep breath in the streets”). Within two decades, the company had remapped the world, catering to a new generation of time-rich, cash-poor twenty-somethings with a penchant for banana pancakes.

Like the Baedekers before them, Lonely Planet guidebooks were occasionally name-dropped in works of literature. Alex Garland’s 1996 novel The Beach, set in Thailand, alludes to a whole culture of Lonely Planet travelers inadvertently reshaping the destinations they passed through. In the process they created what became known as the “banana pancake trail,” a network of cheap guesthouses and cafes in Southeast Asia whose spiritual home was Bangkok’s Khao San Road.

The books also attracted notoriety. In the 1980s, Lonely Planet’s Africa on the Cheap was banned in Malawi for its criticisms of the country’s president, Dr Hastings Banda. Twenty years later, during the Iraq War and its aftermath, the US military allegedly used Lonely Planet’s 1994 Middle East guide for information on the economy, government, and important embassies and buildings. “It’s a great guidebook,” reflected US Ambassador, Barbara Bodine in 2007, “but it should not be the basis of an occupation.”

In the shortened attention-spans of our modern interconnected world, the guidebook’s obituary has been written at regular intervals since the turn of the 21st century. Yet despite existential threats from blogs, booking websites and, more recently, pandemics, there’s something fundamental about guidebooks that still resonates. Standing the test of time, they act as poignant reminders of our life on the road, each one telling a unique and deeply personal story.

You might also like:

How to prepare now for the trip of your lifetime (once the pandemic is over)

Missing your backpacking days? Why not adopt a hostel?

History’s most famous explorers and their epic journeys