It was a sign that I saw everywhere in Morocco. Spray painted onto bus stops, scribbled on restaurant walls, and etched onto the sides of Arabic drums. And now it was here, nearly 4000m above sea level in the heart of the High Atlas Mountains.

Berbers of the mountains

A boulder by the trail is emblazoned in crimson. It depicts three feathered brushstrokes as if painted by the wind that is howling shamelessly around us now. Roughly, the symbol looks like a man reaching towards the sky.

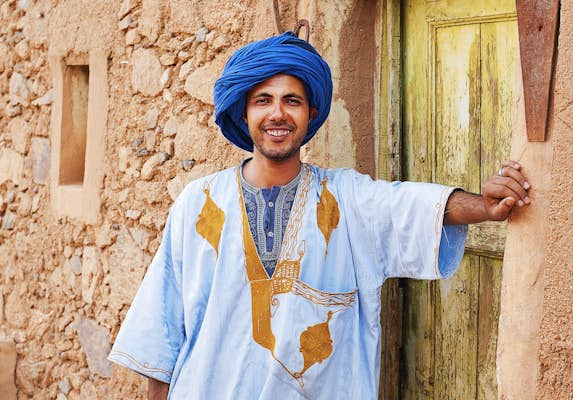

Badr and Mohammad, our local hiking guides, are waiting patiently for the rest of our group to catch up. “What does this symbol mean?” I ask.

“It means freedom,” Mohammad tells me, adjusting the colourful scarf around his forehead. “It’s the sign of the Berber people; it’s on our flag,” Badr elaborates.

I am leaning against a rock, massaging my aching thighs. It is hardly daybreak, and we are already descending from the summit of the highest mountain in North Africa. Badr and Mohammad had led our group up the steep scree slopes of Toubkal in the middle of the night. We had reached the summit breathless, just in time to watch the birth of the new day over the horizon. It came in a bright vermilion blaze, which illuminated the craggy face of the Atlas and all of her jagged peaks.

Read more: How to climb Toubkal, Morocco’s highest peak

The rest of the group have caught up, and are now gathered around the mysterious symbol.

“The Berber flag is split into three colours,” Mohammed explains, retrieving a bag of peanuts to offer us. “Blue, for the Berbers by the sea. Yellow, for the Berbers in the desert. And green, for the Berbers of the mountains.”

We begin to walk again. For us, the strain of the hike is a once-in-a-lifetime experience, but not so for Badr and Mohammad; they trek to the summit at least twice a week. The terrain eases as we descend into the verdant cusp of the valley. Farmers herd their goats about the fields, with the animals grazing lazily under the sparse shade of juniper trees.

Badr is walking beside me, and I ask him once more of the symbol that means freedom.

“It’s not just Berbers who are free. Its Moroccans, Arabs – it’s all people.”

“But what is it that makes you free?”

“What makes you not free?’ Badr replies with a grin.

We hug the side of the trail as a train of mules, saddled in technicolor fabrics, passes us by. “To answer your question, you have to tell me your definition of freedom. Each person has their own.”

I cannot think of one, so I ask Badr for his. He thinks pensively for a moment.

“To work, but not too much.” He responds. “To have time for myself, for my friends and my family. That is all.”

The trail is now at an easy plateau. A village, with its apple orchards and sound of school children singing, would soon be upon us.

Badr’s question sticks on my mind like baklava. What makes you not free? And what does freedom mean? And I wonder what I can learn about freedom from the Berbers; the “free people” of Morocco.

Read more: The best hikes in Morocco’s High Atlas Mountains

Berbers of the sea

It’s not until I am in the fishing town of Essaouira before I encounter the mysterious symbol again. I see it in a music shop, inked on the membrane of a snare-drum decorated with various Berber signs. Hajji, the shopkeeper, picks up the drum and begins tapping a rhythm.

“Play it like this,” he instructs me, passing the drum. “Like a horse trotting. Chk-a-chk-a chk-a-chk-a. Yes, that’s right”.

Hajji takes a guitar and begins to pluck the deep, hypnotic trance of Gnawa, a musical style that hails from the region. The notes resound from the bass; rich, warm and mesmerising, like the dancing flames of a campfire.

Hajji shrugs when I ask him of the curious signs decorating the drum. He tells me that they are ancient Berber symbols. He cannot tell me what they mean, says he knows somebody who can.

Read more: Where to find the best street food in Morocco

I weave my way through the medina. The streets are lined with markets selling glassy-eyed fish, slick from the ocean. Seagulls beat their wings overhead, throwing lofty shadows against buildings as white and dappled as sea foam. I find local artist Younes at his workshop, tucked away in a corner of the medina. He is calligraphing a goat-hide canvas, tracing the elegant hooks and curves of Arabic script. The walls are covered with cured animal skins, depicting artworks comprising some of the strange symbols I saw in the music shop. Younes teaches me that the signs are derived from the traditional face tattoos of the Berber women in his community.

“I was always curious about the symbols when I was younger. But today, fewer and fewer people understand what they mean,” explains the artist, with a melancholy smile.

Indeed, the threat to Berber culture is a real one. The written form of the Berber language, Tifinagh, has widely fallen out of usage. Although there have been some efforts to reintroduce the alphabet in schools, the future of the language remains uncertain. Additionally, Berber people are becoming increasingly pressured to abandon their nomadic lives and small-town living in favour of life in the modern world.

“People move to the city, they get cell phones and they forget their way of life,” Younes elaborates.

I begin to wonder, does this transition come at the cost of culture? And ultimately, the cost of freedom?

Younes smiles knowingly. “Freedom is not a place or time. It’s something behind that – it’s in our philosophy, it’s in our way of breathing,” he pauses, taking a sip of coffee. He gestures to a symbol on the canvas that looks like an anchor.

“This,” he explains enthusiastically, “represents the fusion of Arabic and Berber cultures. There is a freedom in unity, in togetherness. The jacket I’m wearing was made in Italy. Next year, I might wear one made in France. We may change our clothes, but it’s still us.”

“And what does freedom mean to you?” I ask.

Younes chuckles. “This is not an easy question, you know. The sign on our flag simply means ‘be free’. It is a general idea, a way of being. To me, being free means knowing that nobody can choose our place. Nobody can make us happy. Only us.”

Read more: Essential Moroccan experiences you won’t want to miss

He points out another symbol – a rising sun and a key – on the canvas. “The happiness and prospects of tomorrow, and the keys to unlock them. Freedom is also doing something for someone without expecting anything in return.”

Next, he gestures to a symbol of a cat with a crescent-shaped head. “No doubt you have seen many cats around the medina. People feed them, they care for them. But do they expect something from the cat? No. The love is unconditional.”

Finally, he points to a symbol which looks like musical notes. “Three women dancing,” he explains. “This means ‘be in the moment’. You never know what could happen the next day, the next hour or even the next minute. There is no sense in worrying about things out of your control. To be free, you must be present in the now.” Younes drains the last of the coffee.

“And you? What does freedom mean to you?”

Again, I find myself unable to answer.

Read more: Why Tangier should be your first port of call in Morocco

Berbers of the desert

There is no more road after the oasis town of M’hamid, only the endless sea of the Sahara. At sunset, the sand is sumac under a sky flushed magenta. The desert stretches out to meet the skyline, enclosing the town in a hot, fiery womb. Light and shadow dance in the contours of the terrain like yin and yang.

I meet my Saharan guide Aziz at his home. It’s the last house before the oblivion of the desert begins. Aziz and his family are some of the last Saharan nomads. They wandered the desert for generations, herding livestock and moving with the seasons.

Aziz greets me warmly and pours a customary cup of Moroccan mint tea. We sit in the kitchen, sipping the sweet, warm drink and discussing life in the desert.

“Time doesn’t exist there. I don’t even know when I was born!” he laughs. “My mother thinks it was September. My sister thinks it was January.”

Aziz speaks with mixed emotions about life in the desert. One decade ago, he and his family were forced to abandon their nomadic life and relocate to the town of M’Hamid.

“It became very difficult to survive. The Algerian border became more tightly controlled. If some of our camels crossed the border in the night, we couldn’t get them back.” He refills our glasses, drawing the teapot up high and letting the tea cascade into our cups. “I don’t think borders should exist. Anywhere,” he says.

Looking out at the Sahara, it seemed indeed bizarre that an expanse so endless and unbroken could be cleaved by boundaries at all.

“The second reason we moved is that the river Draa began to dry up.”

Aziz tells me that the river had stopped flowing due to the building of a dam in Ouarzazate. As a result, life for desert nomads became increasingly difficult.

“Eventually, it just became too much.”

The next day, Aziz takes me to the place where the Draa is meant to be. Nothing remains but ripples in the sand. Few families maintain a pastoral life in the desert today. But with the unique set of skills needed to survive as a nomad in the desert, Aziz believes that his generation could sadly be the last.

“So what does it mean to be a nomad who is no longer nomadic?” I ask.

“My parents and grandparents feel like they are in prison. They miss the desert. Even now, if I show my mother a photograph from the Sahara, she knows exactly where it was taken,” he says with a grin. “I take her back sometimes, to visit.”

“And despite giving up your way of life, are you still free?” I enquire.

“We try to stay independent. We don’t keep money in the banks, and most of us don’t vote. We don’t like to be controlled. I have an uncle that lives in France now. He married a French woman that visited as a tourist. But he is still free, even if he doesn’t live in the desert. Freedom is more about the way you think. To not worry too much about the future, to enjoy what you have today.”

That night, we sit in the stillness beneath a sky as black as molasses. The only noise is the gurgling of the shisha that we are sharing.

“If you could go back to living in the desert, would you?” I ask, breaking the silence.

“Yes,” he says, without hesitation. “Yes, I would.”

Aziz offers me the mouthpiece of the shisha. I breathe in the tobacco, letting the sweet smoke fill my lungs. The charcoals glow, as bright and hot as a desert sunset. I think back to Badr’s first question that had caught me off guard in the Atlas Mountains. “What makes you not free?”

I recalled what my fellow hikers had to say when I asked them the same question. Apparently, there was too much that stood in our way. The nine-to-five grind, debt, and the stresses of life in the city were all too confining.

Lasting reflections

My last days in Morocco are spent staying with a Berber family along the Hāhā coast. The village is certainly a far cry from life in the city. It’s a simple cluster of stone buildings. Goats and donkeys mosey around the yard, languid in the heat of the sun. The village overlooks the swelling ocean, and the tree-spangled cliffs that trace the shore.

I stroll along the beach with Mohammad. His three pet rescue goats potter along behind us, leaving a trail of hoof prints in the sand.

“We have nearly nothing” Mohammad says earnestly. “For example, I don’t have your passport. But if I choose to think only about that, I would cry. I would always be unhappy.”

Yet, Mohammad and his family show me Moroccan hospitality at its very best. They greet me like a long-lost family member, teach me how to cook traditional fish tajine, and take me to watch a breathtaking sunset over the coast.

It had become clear to me that freedom is not about what you do or don’t have. I finally had an answer for Badr’s question. There was only one thing standing between myself and freedom: me.